Sondheim in the City

She dreams, she arrives,

she walks at dawn,

she lives uptown, she longs downtown,

she gets married,

she’s sorry, she’s grateful,

she walks up Broadway,

and whistles down Fifth,

she can foxtrot.

She won’t make it a crime.

She is… A Sondheim Woman.

About the Album

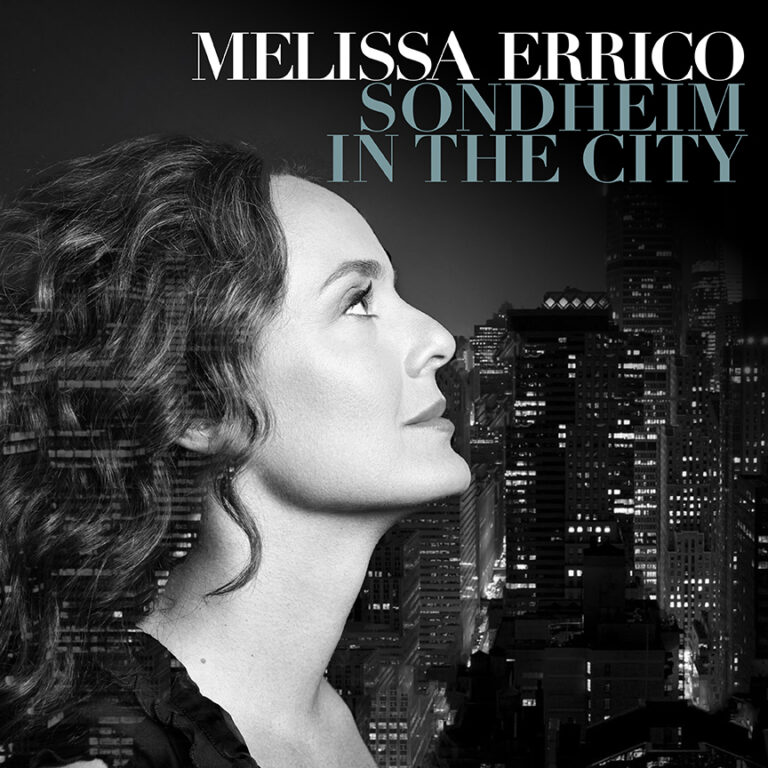

“The finest all-Sondheim album ever recorded,” was The Wall Street Journal’s verdict on Melissa Errico’s ecstatic, inward-turning Sondheim Sublime (released in 2018). Now, her new tribute to Broadway’s greatest songwriter, Sondheim In The City, changes tone to offer us a more outward-driven, kaleidoscopic street fair of New York scenes and moments – summoning back to life the poetic vision of a man who once confessed that his entire creative life had been spent in a twenty-block radius of Manhattan.

Sondheim in the City, Melissa Errico’s tribute to Sondheim’s urbanity, feels like a New York house tour of thrill and heartbreak. In songs like the jangly ‘Another Hundred People,’ the exuberant ‘What More Do I Need?’ and the dry, disappointed ‘It Wasn’t Meant to Happen,’ Errico, one of Sondheim’s deepest-hearted yet lightest-touch interpreters, evokes both the city and cabaret style at its best. On the pristine recording you can almost hear the martini glasses clink — and shatter.”

“With Sondheim In The City comes a short film for her version of ‘Good Thing Going’ from his magnum opus, Merrily We Roll Along. Drawing on Annie Hall (her fashion certainly takes a cue from Diane Keaton’s Oscarwinning role) and French new wave, the dramatic ‘Good Thing Going’ mini movie reflects on the dissolution of a romance between an actress and her director. Errico’s phrasing imbues the tale with the bittersweet sense that perhaps this relationship was bound to fail from the start — but still worth mourning.”

Joe Lynch

“On this 57-minute recording, Errico et al do themselves proud, they do Mr. Sondheim honor, and they do The City just right. But let’s be honest, here: Melissa Errico always does it just right.”

"Melissa Errico is the ‘Sondheim Woman’ in Sondheim In The City. Devoted to Stephen Sondheim’s songs about New York – from the beginning of his career to its climaxes – Melissa’s latest album highlights Sondheim’s artistry while she inhabits one leading lady after another. From uptown to downtown and from sophisticated skyscraper heights to naïve basement depths, Sondheim In The City is a celebration of New York and its legendary musical theatre composer from the extraordinary Broadway star that Billboard magazine calls the ‘premier Sondheim interpreter.’"

Track List

1. Dawn*

(from the unproduced film, Singing Out Loud)

Rilting Music, Inc. (ASCAP)

2. Another Hundred People*

(from Company)

Herald Square Music, Inc. (ASCAP)

3. Opening Doors / What More Do I Need? #

(from Merrily We Roll Along)

Rilting Music, Inc. (ASCAP), Revelation Music Publishing Corp. (ASCAP)

(from Saturday Night)

Burthen Music Company, Inc. administered by Chappell & Co. Inc. (ASCAP)

4. Take Me To The World*

(from Evening Primrose)

Burthen Music Company, Inc. administered by Chappell & Co., Inc. (ASCAP)

5. Can That Boy Foxtrot! #

(Cut from Follies)

Herald Square Music, Inc. (ASCAP)

6. Anyone Can Whistle #

(from Anyone Can Whistle)

Burthen Music Company Inc. administered by Chappell & Co., Inc. (ASCAP)

7. Everybody Says Don’t #

(from Anyone Can Whistle)

Burthen Music Company Inc. administered by Chappell & Co., Inc. (ASCAP)

8. Good Thing Going*

(from Merrily We Roll Along)

Rilting Music, Inc. (ASCAP), Revelation Music Publishing Corp. (ASCAP)

9. Broadway Baby #

(from Follies)

Herald Square Music, Inc.

10. Uptown, Downtown #

(Cut from Follies)

Herald Square Music, Inc.

11. It Wasn’t Meant To Happen #

(Cut from Follies)

Herald Square Music, Inc.

12. The Little Things You Do Together #

(from Company)

Herald Square Music, Inc.

13. Sorry-Grateful #

(from Company)

Herald Square Music, Inc.

14. Being Alive *

(from Company)

Herald Square Music, Inc.

For all songs: Music & Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim

# Arranged by Tedd Firth * Arranged by Rob Mathes

Press

Liner Notes

Revisiting Sondheim

It was a Monday morning in July of 2023, and I was able to get an appointment to see Stephen Sondheim’s home, newly on the market. I couldn’t possibly afford it. Wishes come true, not free. I was on the wishing part.

Walking into the house, I immediately sensed a touch of the pre-Raphaelite. The foyer is dark and narrow, a wood-paneled tunnel with a deep blue tiled ceiling, a kind of night sky effect, with dark sconces. It reminded me of the interiors at college, where dark wood told you to enter a meditative state, to turn inward to your books, within a sort of glamorous byzantine library. A small kitchen with metal cabinets and not much space made me think cooking was not one of Sondheim’s key activities. Across a pleasant living room, more for reading than music-making (no grand piano in this room as you might expect for salons), sat a round table, more like a poker or card table than for children eating cereal or pizza with friends. The home was an adult home, a man’s home, and it was beautiful.

For one hour, I imagined myself living there. This was not only a chance to look at his home, but also to do what you do when you visit a home. You picture your life overlaid on the life that shaped it before you came along. Where would I cook? Where would my third daughter sleep? Would I use the terrace? Would I have a dinner party in that lovely dining room? Where would we watch a family movie? Do we ever watch family movies?

I walked through Sondheim’s rooms, imagining my own life overlapped with his now quiet home, where he created things bright and beautiful. And now he’s gone, in body. But the house—just entering the house—was like walking into a cathedral in Europe. The sudden change in temperature, the cool stone, the sense of expanse, the gothic ceiling hovering overhead—that feeling of entering an almost sacred space.

Of course, his home is not in Chartres or Reims, just a nice townhouse tucked on the south side of 49th Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues. I had trouble imagining my girlish teenagers there, and soon I stopped repainting it white in my mind and adding colorful pillows and sunflowers. I just started walking through the home and felt meditative and respectful.

I didn’t study the objects, the many posters and displays of antique cards and board games on the shelves and walls. But there was a luxuriance in the cards and their design that appealed to my love of medievalism, reminding me of countless hours at Yale looking at the work of Bonifacio Bembo in the dimly lit Beinecke rare book library, and also the many trips to strange little palazzos and side chapels as a traveling art history student.

In the back of the living room, there were a few steps that led upwards to the dining room and its grand dining table. It was surely the place for endless hours of conversation. I imagined Patti LuPone and Elaine Stritch, Raúl Esparza and Donna Murphy—Bernadette! Maria Friedman! Even Streisand!—and playwrights and orchestrators and aged movie stars and wicked directors, all laughing and outsmarting each other. Veterans, warriors, and dreamers, stung but still hopeful, angry but still capable of being turned back by music to become fluid, racing wet souls, despite seeming parched and a bit cruel. I imagined—and could hear the voices of—a community that belonged there. The faces of the city that loved him and looked up to him.

His presence was always so powerful. He was more than the man behind the curtain to all of us, more than the almighty Oz who turns out to be ordinary. He was human, yes, but he also built Oz. His work was the shining green city, in sound and characters and standards and ideas. It all shone for us and intimidated us and inspired us to join in, to walk our yellow brick roads to any place near him. We loved him for both his magic and his humanness. We were at once afraid and excited to hear what he would say after a performance or a concert.

Would Sondheim be critical? Well, yes, of course he would, but would he come backstage? He was an enigma. He was shy, and he was strong. I shared a few awkward moments with him in person, and then many easy emails with him. In candid communications, we flowed back and forth, brisk and spontaneous, funny and personal. When one of my New York Times essays was published, he berated me for letting Carol Lawrence tell her West Side Story story as she recalled it, and after much back and forth, he replied, “You are more generous than I.” He told me he could indeed whistle, and he advised me to be less self-deprecating: “It is your most unattractive quality, and I am the champ.” He always asked about my children. The few times I saw him in recent years, it was clear he had so much love in his life, with his husband standing nearby, utterly warm and patient as everyone hung on Steve’s last word.

My heart stopped on the second floor where his piano was, the room with the dark green wall, the room with the sofa he reclined upon in image after image, under the stained glass. I gasped. The room looks out onto the garden and possesses a kind of calm—it is a prayer-like space. I couldn’t help but think of it as a part of his music, that I had always sensed: the sublime and prayer-like Sondheim.

When I planned to record my first album of his songs, Sondheim Sublime, it came to me as an impulse. To be honest, it struck me as obvious, something that would be easy and natural. The idea of “easy,” of course, was constantly struck down as I approached each delicate and intricate detail of his art.

Adding to the complexity at that time was my own home—my body. I had found out I had a health concern, and I had to have multiple surgeries and tend to it. While facing some potent realities, I decided I really must make a Sondheim album, as a kind of letter to—if required—leave behind to my daughters, my family, and my peers. I remember thinking of Sondheim’s work as a castle with many rooms and that I was going to explore only one: the “sublime” room—the one devoted to lyrical sounds, to empathy and philosophy. “We die but we don’t,” I hoped.

Back to the present, with me standing in Sondheim’s house, years later. In the sublime chamber I had never actually seen in person: the study, the piano, the stained glass, and the dappled sunlight where a genius could recline and work with his many pencils to shape a rhythm into song. I feel so different now. Not only am I seven years into my restored health, but a couple of years out of the shared pandemic.

I often thought about Manhattan as it ended, a city with its bruises and troubles. I thought of all the ways the city spoke to us during that time—the suffering, the empty theaters, and the musicians who couldn’t play. Creativity found Zoom. We celebrated Steve’s 90th birthday with a live-streamed concert viewed by a few million people, in which I was honored to sing “Children and Art” literally moments before making dinner for my quarantined children.

When the city re-opened, I did a concert at my favorite nightclub that invited me to participate in its reopening in fall 2021…before the Delta variant halted us again. I decided to sing about Manhattan: why I came to this city and what it means to me. I wanted to protect my own memories and rebuild a love and trust in what makes living here so breathtakingly complex and immediate, essential and kinetic, electric and life-giving, primal and fertile, awful and perfect, our Oz. Take Me To The World. I turned to Sondheim.

This new album—Sondheim in the City—is his New York and mine. Making this recording, my stories got intertwined, tangled, buried, lost within it. My life came into sharper focus, as clear as—a rare Sondheim gem many will not have heard!—“Dawn.” Steve once said, “I was born in New York City. In the middle of Manhattan. I have lived my whole life in what amounts to twenty square blocks.” Well, I was born in Manhattan, too, and learned to walk in Washington Square Park, then rode the train when we moved to Long Island—truly thousands of trains—with a lust like no teenager ever had for a city. I sing that erotic, crazed identification with the speed and deceits and battered barks of this city in “Another Hundred People,” hammered in such a funky arrangement by my producer Rob Mathes, drummer Lewis Nash, and our brilliant band led by Tedd Firth. As an aspiring (then perspiring) actress, I have lived “Uptown, Downtown” (six times), been married in Central Park, welcomed three daughters into the world, lost one child in the same New York hospital, and just marked my 25th wedding anniversary.

And so, I “drew” my house over his. First, I found my ancestors who came over by boat, via shipwreck, from Italy in the late 1800s, and my Ziegfeld roots. The showgirls in the family, including my grandmother, and her sister, the breakout star Rose Mariella, who was discovered in a subway chain sandwich shop. She could be the very girl described in the lyrics to “Broadway Baby,” in my own family! As Follies felt like home, I stayed and played with more of its cut songs, and three appear on this album: the sexy relationship (“Can That Boy Foxtrot!”), the gut-wrenching breakup (“It Wasn’t Meant To Happen”) and the two-in-one misery of “Uptown, Downtown.” It’s all my New York. The deeper I went, I began to imagine myself as the subject of my own John Updike-style novella, a tale of an imaginary me, shot like a 1970s movie starring Jill Clayburgh, that I could call The Secrets of a Sondheim Woman. The poster art would say:

She dreams, she arrives,

she walks at dawn,

she lives uptown, she longs downtown,

she gets married,

she’s sorry, she’s grateful,

she walks up Broadway,

and whistles down Fifth,

she can foxtrot.

She won’t make it a crime.

She is…A Sondheim Woman.

This is not designed as a cast album of his Manhattan shows, but it is drawn from his city-inspired scores. Even the Brigadoon-like town of Anyone Can Whistle gives two portraits of Manhattan: there’s the panic to conform and the necessity to be autonomous (to learn to not be stopped) in “Everybody Says Don’t.” Then, there’s the utter vulnerability of the title song, which could be sung by any of our favorite Manhattan neurotics. I think of it as the anthem of New Yorkers, who so often are afraid of the simplest, natural gestures while they do extraordinarily learned things. That same ambivalence infuses his songs of sort-of love. I see a lot of Manhattan marriages, and none are simply drawn at this point: “Sorry-Grateful” and “The Little Things You Do Together.” I remember my own desire to get married, though, and wanting someone to hurt me too deep and ruin my sleep, as in “Being Alive”—yet singing this song in my midlife, I gather my life in my arms to sing it, clinging more to the idea of not being buried by life’s setbacks, than to Bobby’s first dance with commitment.

I hope listeners will step into my imagination and walk into my dream city. There’s nothing looming or overwhelming in “Another Hundred People” —I focus on pure appetite, to be surrounded by a monumental circus of thrills! And I act on this record: I imagine performing it as I’ve been doing for years, with a travelling jazz ensemble, and somewhat in character. For “Broadway Baby,” I imagine myself as a successful film-noir-worthy chanteuse with a wink in her eye, singing breezily to the tables of onlookers, as if to say, “I will never forget what it took to get here, I was this baby and she’s inside me.” I veer from memory to memory, and savor some moments when I was not, shall we say, circumspect, but had a marvelous time (“Foxtrot”) and learned what comes of lost loves that weren’t meant to happen. My voice feels a parallel to “Send in the Clowns” when I sing “It Wasn’t Meant to Happen.” An actress collects her agony. I sing to my teenage girls who have survived a pandemic at their most vulnerable years, and I vow to take them to the world always. In “Opening Doors,” the lyric, Who Wants To Live In New York? / Who wants the worry, the noise, the dirt, the heat?…is me not finished with my ongoing attachment to the city. It is the very sentiment I heard on a rare demo of a young Steve singing about how it’s such a crappy place, but he belongs here, in “Nice Town, But—,” my absolute ticklishly favorite unknown from Climb High, which I hum in my mind, seeing myself rushing to catch a subway, coffee cup in hand. I step into Sondheim’s city easily, with hope that it will heal from hard times as it always does. “Dawn” is that hope, a prayer, for renewal. Hope is my companion as we stroll the streets, both halfway between yesterday / And tomorrow… / Not a street that doesn’t have a shine / Not a sound except the milkman’s rattle / Not a stream of seven million cattle/ And the city’s mine.

Ambivalence is Sondheim’s compelling great theme, of course. On stage, I’ve often called it “the Sondheim comma,” meaning the way he balanced contrasting emotions on a single point. On Sondheim Sublime, those ambivalences were often internal, felt inside a single life. On this new one, they’re more external, outward facing statements about the way we treat each other in a crazy and compressed city. Exploring these songs I wondered: Does the kind of ambitious, emotionally and morally serious musical theater Sondheim embodied have a future? Is his charming, claustrophobic New York still the New York my children will inherit, if they even want to live here? Has the city become ever more monotone and uniform? Have Sondheim’s ambivalences been replaced by simple aggression? Would the lady in “Uptown, Downtown” who divides her life between both ends of the city even be able to tell the difference anymore, when uptown and downtown have become so homogenized? And perhaps most pressing, how do we keep Sondheim in the front of the line?

By singing him. If Everybody (ever) Says Don’t, I say Do. I was and am alive here, and I have one poet who speaks so much of that for me.

— Melissa Errico