– David Zippel, lyricist City Of Angels

About the Album

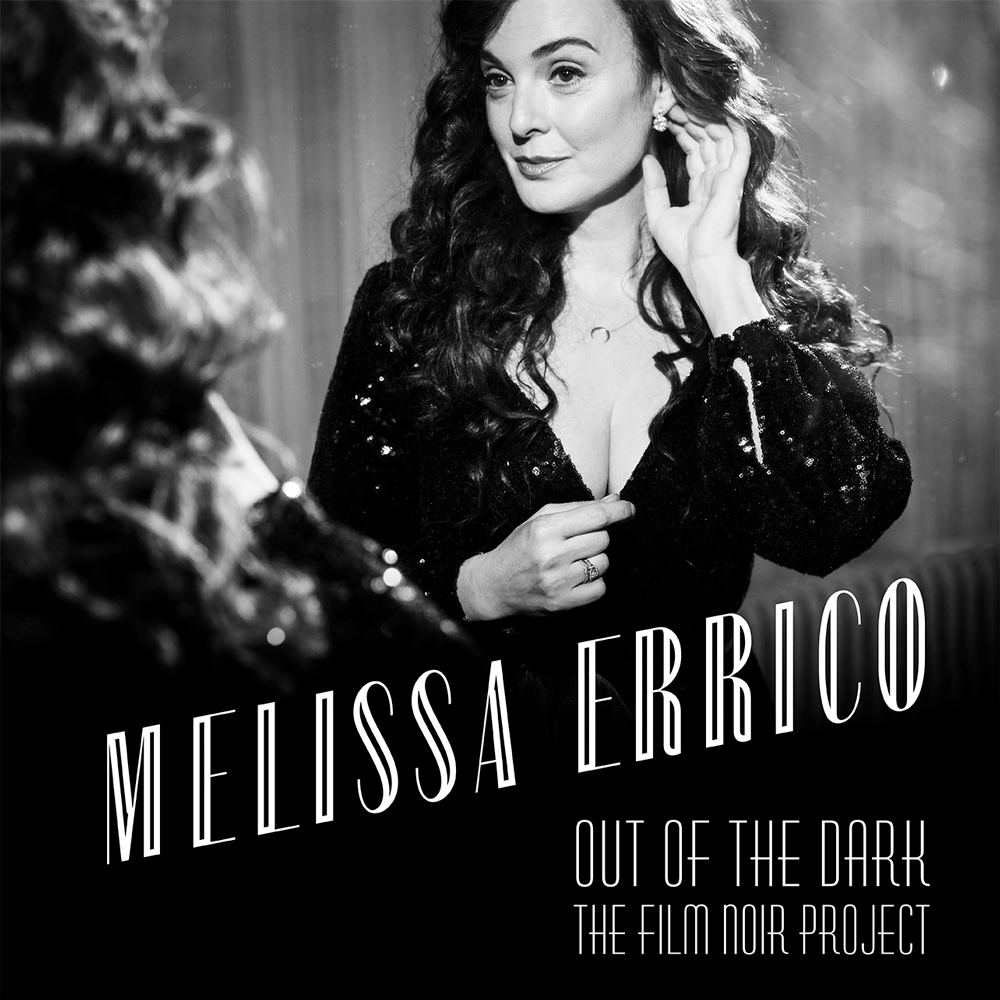

At the height of the pandemic in 2020, with all the world locked away in lonely rooms and only old movies to watch at midnight, singer and author Melissa Errico suddenly returned to one of her life-long obsessions – noir! That dark, disturbing sensibility of intractable fatalism that Paris existentialists discovered in American film in the nineteen forties, and that runs as a mesmerizing, mysterious current through modern movies and modern music alike. Along with her collaborator Adam Gopnik, she curated a series of film noir classics at New York’s FIAF, appeared in the New York Times with an essay on having a black sequined gown specially made to play the role of the femme fatale on stage and offered Manhattan a concert of noir songs.

Now, her recording “Out Of The Dark: The Film Noir Project” brings together all of those threads in a single masterly sequence, a song cycle that offers an unforgettably sexy, sensual, and sophisticated arc, all black-velvet piano and vibraphone tones, telling a complete story of hope, despair, and hope renewed. In no sense a retro project, her choices reach from noir classics, like Laura and The Bad and The Beautiful, into the French chansons of the fifties and sixties, and includes the debut of four entirely new songs, by Michel Legrand, David Shire, and the late Peter Foley, all with arrangements by her musical director, pianist Tedd Firth.

Errico’s dream was to paint a picture of an era now made mythological – the world of the 52nd Street jazz club, of the doomed and unfathomable chanteuse, of nightclub gangsters and exiled French poets – that would somehow speak to today’s condition. “Did you ever have the feeling that the world has gone and left you behind?” she sings in the rarely recorded verse of Matt Dennis’ “Angel Eyes” – and at a time when that feeling has become so universal, she sends us back into the past and forward into the future to affirm, as one new song suggests, that “darkness is all we have to show the shapes that light can make.”

Track Listing

Side A

- Angel Eyes

- With Every Breath I Take

- It Was Written In The Stars

- The Bad and the Beautiful

- Haunted Heart

- Amour, Amour

- Silent Partner

- Farewell, My Lovely

Side B

- Laura

- Blame It On My Youth

- Checking My Heart

- On Vit, On Aime

- Solitude

- The Man That Got Away

- Detour Ahead

- Shadows And Light

- Again

Out of the Dark

0:52

1:33

1:17

1:50

1:36

1:06

1:35

1:14

6:52

1:39

Notes on Noir

All through the pandemic year of 2020, I kept falling into an old obsession of mine, one that I’d kept, and sporadically indulged, since college—watching film noir of the 40’s. (I was an art history major back then and fell wildly obsessed with the genre while taking a semester of film studies—especially when I heard the song “Rififi,” which I knew I needed to sing onstage someday.) Every night, after my husband and my three daughters were asleep, I’d turn to an old film for some kind of… What? Escape? Comfort? I watched many films, mostly American, but some French: Out of the Past, Daybreak, Nightfall, and Two Men in Manhattan. There I was, watching these films while we were all trapped inside, and yet… like the lovers in those films, we were fascinated by our own entrapment. It seemed we were all finding something surprisingly beguiling in it, instead of only being disturbed by those emotions. There was something seductive about our own isolation.

Then, in the summer of 2020, I was asked by the French Institute/Alliance Française (FIAF) in New York to present a virtual concert to the world. Their first request was, “Could you please begin with the art of seduction? Our audiences love to be seduced.” Immediately, I offered them the theme of film noir, and they agreed.

I joked on Zoom, “Oh, you want seduction, then we end with noir… so how about a 3-part series called LOVE, SEX and MURDER?”

“Wonderful!!” exclaimed Marie-Monique Steckel, the president of FIAF, from her Zoom square in the south of France.

After I logged off, I knew I could fulfill the musical side of their request… but for further enlightenment, I turned to my frequent collaborator, the essayist, novelist, and lyricist Adam Gopnik. Our discussion led to insights and ideas, and a door of creative possibilities was flung open. He suggested the more demure title, Love, Desire, and Mystery, with the aim to present a concert with dialogue between the songs, illuminating each topic with references to history, poetry, love letters, and key French or Franco-American figures in art and literature.

Adam and I share an art-historical passion for this kind of cinema, but we were also convinced there was a parallel between the genre of noir and the pandemic world we were sharing, both living with our respective families, in the Manhattan area. Manhattan!—which had become desolate, with empty theaters and barren streets. As often with our projects, a flurry of inspiration happened when we hit on good ideas, understood passionately and prismatically. I seemed to hit a chord in Adam, enough so that he agreed to join me on stage, with his guitar in hand. He and I even prepared a film festival to coincide with the final livestream, Mystery, performed on May 6, 2021.

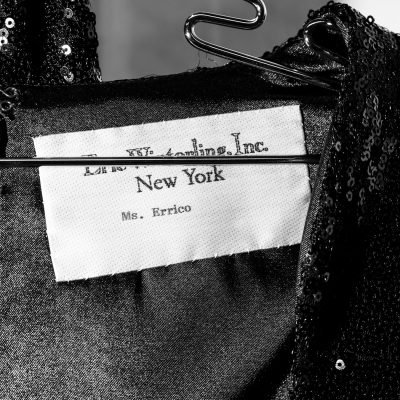

I was suddenly fulfilling a lifelong dream—to perform a film noir concert. And in the show, I would take on the persona of a femme fatale. This occasion required the perfect gown! After stumbling, I made a phone call to premier Broadway designer Eric Winterling. He offered to make me a stunning, black-sequined, film noir dress.

His atelier was closed; Broadway was still dark. As his assistant took my measurements, whispering that she was delighted to help, she told me, “You are the first actor I have seen in a year.” I wrote an essay about the making of the dress, the man behind the design, and the shop, forced into quiet. That article was published in The New York Times on May 4, 2021. The noir dress and the music came together. Of course, what mattered the most to me in this concert was the music. How would I sing film noir? I felt I knew internally what that was, more than I could explain it.

Finding my voice…

Finding my inner femme fatale…

Why this urgent need to sing her… to step into her… to become a femme fatale for 2021? I meditated on noir themes and discovered that noir is a French term for an American art form. Noir, I felt, was about omnipresent corruption, the implacable nature of fate, the quality of destiny, and people who are doomed by their own desires.

In Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, perhaps my favorite noir film, the characters are obsessive romantics, knowing that fate will sooner or later cut their throats. Jane Greer, in a white dress in a Mexican bar, is nothing but bad news, and Robert Mitchum knows it. She will be the death of him, but he cannot resist her. I couldn’t stop thinking about being trapped, like in Elevator to the Gallows. Trapped. I was haunted by the score, composed and played by Miles Davis… the music of loneliness and disillusionment.

I had a feeling for what noir sounded like, but I imagined it stretching out of the 1940s, both ahead of and even before that era. The essential sound I can only describe as… a longing, a sinuousness, meandering chords, major and minor changes… the simplicity of a small band, in the world of just a lonely pianist and a girl. Feeling the world with very little… a sparseness in the music. The single saxophone. Vast emotion. The nightclub glamour. One whining trumpet told the whole story in Elevator to the Gallows. The economy of pain. It’s almost anti-operatic. Tedd Firth and I work that way, sometimes in a little nightclub, and we give it our all, no matter how few people might be there; it’s a jazz ethic.

So, we performed the noir concert, setting songs and ideas to the stage in our bold experiment. It was beautifully received… with many people urging me to record the show! And so, I set out to do that, knowing the key to a recording project might be to somehow balance the nostalgic, delicious, rear-view-mirror quality with something neo-noir, contemporary, related to our pandemic life, eternally present.

In a way, a surrealist conflation of past and future.

I looked for songs that captured the feeling of implacable fate and doomed, obsessive love. Noir for me was a mood, not a moment. Some of the songs that came to mind pre-date film noir, such as Oscar Levant’s “Blame It On My Youth,” which, to me, isn’t just about the sadness of a break-up, but also a woman’s discovery that her life was bound to be that way. She is irrevocably haunted by the guy, instead of just broken-hearted.

Matt Dennis’ “Angel Eyes” is more of a classic saloon song, like “One For My Baby,” about a broken heart at three a.m., but I thought I could maybe find the sardonic inner laughter of the singer, which is what moved me. I heard in that song a more fateful twist, especially once I found that rare opening verse, which almost no one sings: “Did you ever have the feeling that the world’s gone and left you behind?”

“The Man That Got Away” belonged to Judy Garland, and always will, but I imagined it as an art song, rather than a driven song. The man got away, and he was never going to be there. He left anyway. But she always knew it. Fate.

The writer Jeremy Sams agreed to translate a wild, entangled, somewhat creepy melody from the film Peau d’Âne, giving me a Michel Legrand world premiere in English, with lyrics that speak of how love will drive you crazy. I also thought it would be great to get an original song written by a theater writer, and my friend Peter Foley delved right in. He wrote a modern theater noir song, “On Vit, On Aime.” Peter enjoyed seeing the livestream of the concert, but, sadly, died last summer, tragically young, before he had the chance to hear the masters of the album.

I returned to a modern song by Patricia Barber called “Silent Partner.” Though it is completely contemporary, I think it captures the feeling of obsession. A woman is both lost to herself and inviting her partner—a state of being lost and found at the same time. Ideas like this set my soul on fire! And my voice.

In creating this album, I hoped to capture the year of noir cinema watching, of an interest in the sensibility of… a life unplanned and inescapable. I call it Out of the Dark: The Film Noir Project because it has been a project—of performing, of outthinking the pandemic, and of finding a way to perform in a time of challenge and social distance. It has been a way of singing and writing. (The character I created during this process actually galvanized Adam into giving the project an extra twist… a novella, a piece of noir writing by him, inspired by the track list of the album, twinkling with mischief, offering me the seed of a theater and concert project.)

As I write these notes, the pandemic has returned, even when we thought it had passed, unplanned and inescapable in ways we never imagined. We never thought we would get caught in a 1918-style pandemic… any more than Robert Mitchum thought he’d get caught in a fatal love affair that would delight and doom him, which is the story of every film noir. A doom you cannot escape and a delight you cannot reject.

This album is a collection of all that energy reconsidered—pieces of a black and white world, held in many hands and minds, spun and turned and relished—to express my most profound hope… for light.

—Melissa Errico