English Edition, expanded from her New York Times memoir published in January 2019

As first published in La Regle Du Jeu

I can still hear Michel Legrand’s voice in my head: “Melissa! Hurry! Come!” This was morning at the Music Box Theatre, an early rehearsal during the first previews of the Broadway musical Amour which Legrand wrote and I starred in in 2004.

It was 10:01 am and we were all moving slowly, nursing coffee cups in the palms of our hands. We had performed the show the night before and were still easing into the day. Michel never wanted to waste a minute. He pulled on my arm, speaking fast in heavily-accented English, insisting that we must find a piano. As we scurried to the downstairs theater lobby, he told me he had completed a new song for my character, Isabelle, and it would go into the show that evening. For two days, there had been discussions that the show needed a new song showing how the lonely Isabelle gets lost in fantasy stories and is addicted to novels and magazines, how she turns to them to get lost in dreams of romance and intrigue. I had called my mother to ruminate on this, as she had grown up in the 1940s and 50s and told me how commonplace it was that women listened to radio shows and soap operas to escape their banal domestic routines; she told me some of the storylines she remembered. I mentioned this to our lyricist, Jeremy Sams, at work one day, and, collecting ideas, he listened. Then suddenly, overnight, Michel had written a ravishing melody and a finished song was mine to learn.

After he called me to his side, we flew down the gilded stairs of the theater, and I tucked beside him on the piano bench. What I remember most was the change in Michel’s body language as he shared his new music. Once at the piano, he slowed down and became absorbed. He would rush you as if to an American ice cream parlor on a crowded summer afternoon—and then offer you a slowly simmered French meal. I sat as he played, and marveled quietly when his hands turned the melody unexpectedly, a new minor key, a delicious twist that only he could have invented. Of course, the song “Other People’s Stories” was beautiful, perhaps the best remembered in the show. And it was in Amour by 7:00 pm that night, typed hurriedly by a stage manager and taped into a magazine prop so I could literally read it as I sang it in front of a thousand people.

This mix of wild energy and plaintive emotion, I would learn in our weeks of rehearsal, governed Michel’s extravagantly well-lived life. Music was urgent to him. Well, almost everything was urgent to him—try hailing a New York taxi with him, oh! the impatience—and then at the piano, he was transformed and calm. Stilled by the beauty of his own sublime music.

I heard his voice again in my head on a cold Saturday morning earlier this year when I got a text from the actor Malcolm Gets. “Michel!” is all the text said. It was 8:08 am. Directly below was a link to The New York Times announcement: Michel Legrand had died the night before. I was stricken. Though I hadn’t seen him for some time, he was always in my mind. We have so few mentors and muses in a lifetime, and Michel was one of mine—as, I realize now, I was one of his. That an Italian-American girl from Manhasset (sort of the Neuilly of Manhattan) should have become so intimately involved with one of the greatest of French popular composers—perhaps the greatest French popular composer since Offenbach—now seems to me one of the great strokes of improbable good fortune of a lifetime.

I was born in the early 70s and I cannot recall a day of my life where Michel Legrand wasn’t a part of the fabric of our family. My father is a doctor, a prominent Manhattan orthopedic surgeon, who grew up in a first-generation Italian family in a modest small house in New Jersey with two working parents. My father’s sister was eight years old when she began playing the piano and my father, only four-years-old, grew transfixed by the instrument. He even slept under the piano, just to be near it. By the time he was a teenager, he was an accomplished classical pianist and was accepted at Yale University in 1957 as a scholarship student in music. My father paid for his college expenses by playing the piano at “socials” and university dances, leading bands and mastering the American Songbook from Gershwin to Cole Porter, becoming expert at jazz-based “popular” songs—and impressed by the exciting new sounds of a 22-year old Michel Legrand whose Dionysian album “I Love Paris” was instantly popular with American music lovers who marveled at his treatment of such songs as “Autumn Leaves” and “La Seine.” With 15 songs woven together in a transporting suite beginning with church chimes, the album was a hit in the US, and with my Dad. At Yale, my father met my mother at a party—she approached his piano just as he was playing the Gershwin brothers classic “The Man I Love”—and they have been together ever since.

I was born in the early 70s and I cannot recall a day of my life where Michel Legrand wasn’t a part of the fabric of our family. My father is a doctor, a prominent Manhattan orthopedic surgeon, who grew up in a first-generation Italian family in a modest small house in New Jersey with two working parents. My father’s sister was eight years old when she began playing the piano and my father, only four-years-old, grew transfixed by the instrument. He even slept under the piano, just to be near it. By the time he was a teenager, he was an accomplished classical pianist and was accepted at Yale University in 1957 as a scholarship student in music. My father paid for his college expenses by playing the piano at “socials” and university dances, leading bands and mastering the American Songbook from Gershwin to Cole Porter, becoming expert at jazz-based “popular” songs—and impressed by the exciting new sounds of a 22-year old Michel Legrand whose Dionysian album “I Love Paris” was instantly popular with American music lovers who marveled at his treatment of such songs as “Autumn Leaves” and “La Seine.” With 15 songs woven together in a transporting suite beginning with church chimes, the album was a hit in the US, and with my Dad. At Yale, my father met my mother at a party—she approached his piano just as he was playing the Gershwin brothers classic “The Man I Love”—and they have been together ever since.

Yet my father, for all his passion for music, became a medical student, and soon after graduation from medical school was drafted for the Vietnam War, where he was a medic in Saigon. My parents were separated and had a newborn son, my brother, Michael. One of the songs of their emotional life at that time was the 1964 Legrand classic “I Will Wait for You”—originally “Je ne Pourrais Jamais Vivre Sans Toi” from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. I realize now that it was written about an imaginary couple separated by the Algerian War. It became real for my parents as a song about the Vietnam one, ironically a war inherited by America from France.

Yet my father, for all his passion for music, became a medical student, and soon after graduation from medical school was drafted for the Vietnam War, where he was a medic in Saigon. My parents were separated and had a newborn son, my brother, Michael. One of the songs of their emotional life at that time was the 1964 Legrand classic “I Will Wait for You”—originally “Je ne Pourrais Jamais Vivre Sans Toi” from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. I realize now that it was written about an imaginary couple separated by the Algerian War. It became real for my parents as a song about the Vietnam one, ironically a war inherited by America from France.

For me, from the first, Michel Legrand’s music was above all physical. Its presence literally transformed the room in which it lived. My father, back from Vietnam, would come home from the hospital and play Chopin for hours. But then he would meander over the keys for another half hour or more, playing Legrand. (I thought he wrote “Windmills of Your Mind” until I grew old enough to ask him what those beautiful sounds were. Michel Legrand’s name was mentioned to me with the same seriousness that my father would mention Debussy’s or Ravel’s or Rachmaninoff’s. He revered Legrand and meditated on the exotic chords, playing them as if they were sacred, letting the effect of their sheer beauty wash over our house and over his own spirit. My father was a reticent man, a surgeon ruled by his beeper (a pre-cellphone device attached to the waist of his pants) which would buzz when he was needed at the hospital. He was often very tired and would fall asleep in the TV room fully dressed, his head back on the couch, mouth open, taking a nap right in the middle of our busy home.

But there were afternoons when he knew he wasn’t on-call and had put aside a few hours for his music. I liked to come in, instead of doing my homework, and listen. My father shared the names of the songs he was playing: “Claire De Lune,” a Rachmaninoff prelude or, one of his classical favorites, the “Chopin Ballade in G minor.” I waited for him to get to the stuff I liked the most and that was Michel Legrand, songs such as “Windmills of Your Mind” and “The Summer Knows.” I didn’t quite grasp that the composer Michel Legrand was alive, and, say, that Chopin was long gone. Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Legrand…they all seemed to exist in one historic time. My father told me how he loved the movies they were from but said I couldn’t see them “yet”—never explained the plots, or even played the videos for me. I sensed there was something “grown-up” about The Summer of ’42 or The Thomas Crown Affair, and I wasn’t quite old enough to entirely be let in on all the secrets.

The father-daughter seduction in this coded dialogue was bonding and I loved those stolen hours where the doctor wasn’t running off, or exhausted asleep in his suit. My mother loved the songs too and I can remember countless times where he would play” The Summer Knows,” and she would waft into the living room, perhaps from the kitchen around dinner time, and fall on the sofa in a swoon. My mother was beautiful—a shapely, deeply glamourous blonde woman who worked hard and genuinely succeeded at evoking Anita Ekberg or Marilyn Monroe. She loved when he abandoned the intensity of his classical practice—which she also found ruthless and relentless—and played a Michel Legrand classic like “His Eyes, Her Eyes” or “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?” During my teenage years, I became aware of the erotic and mysterious communication in my home. I was always so happy to see my mom walk into the living room, her body language soft and supple, as she lay down on the sofa, letting her hair fall over its edge. She sometimes seemed aware I was delighting in her, and my father enjoyed his success in thrilling us both. I wanted them to kiss—and she occasionally did come over and give him a big long kiss, as he played somewhat slower but hardly missed a note on the piano.

Michel Legrand was, in our home, a sort of portal to freedom and sensuality. Hiding the plot lines of the movies from me, my Dad winked and smiled, implying by his winking omissions that there was more out there than I knew now. Legrand was a keyhole, through which I saw a light, knowing there were other rooms in my own life to come.

I began my own career as a musical theater performer in 1989 in a French role as Cosette in Les Misérables. I was lucky enough to go on to star in a series of Broadway musicals and, throughout the years, I sang Legrand songs whenever an occasion arose, taking his music to be more of a fact of life than a part of my theater career.

Then, one day in 2002 when I was living in Hollywood, I was approached by my manager in a fancy Beverly Hills talent office. I had done seven failed television pilots, making it my goal to get the number up to eleven as George Clooney had before his first success—thinking that was a magic number where perhaps I could have a break-through. My manager handed me a fax that had just come to the office from New York City. It said that there was an audition in New York and the director James Lapine would like me to come in. Apparently, there was a musical in Paris called Le Passe Muraille and it was transferring to Broadway—with music by Michel Legrand.

The paper seemed to glow in my hand, as if it had a light shining from inside it into my soul. I turned to my Hollywood manager and cried out, “Michel Legrand…Michel Legrand!…wrote a musical!” She turned to me, matching my smile with her own, and said “I know, I know! I love her!”

So, I left that agency and that manager, permanently as it turned out, and flew to New York to follow the promise of that illuminated fax. I called my father at once and told him I had gotten the lead role in a Legrand musical, now re-titled, for American audiences: Amour. James Lapine explained that they had to title it Amour because Americans only know three French words, the other two being “café” and “croissant”. (I wonder what the three American words are that French people know?)

My father, now age 80, still recalls that phone call of mine and his eyes light up, incredulous, at how strange and lucky that life twist still seems: “I knew it meant you, we, might actually meet Michel Legrand.”

And so, we did. I’ll never forget the first rehearsal when Legrand was in the room. I tried to shoot him the warmest smile of my life. I remember thinking I will sing whatever he writes and make it as beautiful as I can, I will serve his talent and give the show everything I had. That was easy: Michel and I had an immediate rapport. I loved the musical and learned what he meant by it being an “opera bouffe”—both somehow classical and yet with the light air of a spoof.

We merged. He often told me he loved the classical purity of my voice and the clarity of my diction. I had been trained to sing clearly, not ‘belt’ or yell, and found the sound of my voice honest and direct, and once he even told me “Yours is the voice I hear in my head when I write.” Our chemistry might also have been built on my willingness to be subsumed in his work. I was tireless and determined to get things right, to work the extra hours of rehearsal, to stay late and join in discussions over changes that James Lapine wanted to make to the show.

Lapine had written and directed some of my favorite Sondheim musicals, including Sunday In the Park with George and Into the Woods. A brilliant and serious man of the theater, I could see him grow frustrated at times with Legrand’s playful and impulsive personality. Michel always had a touch of Dionysus about him, while James was strictly Apollonian. James thought things didn’t work if they didn’t make sense. Michel thought things worked when they didn’t make sense—because they were wonderful in themselves because they sparkled with joy. James wanted to ground the play in logic, and he faced two challenges to that—Michel’s impatient ebullience and the illogical nature of the Marcel Ayme plot, an adaptation of his 1943 short story “Le Passe-Muraille,” set in Paris, in Montmartre, shortly after the second world war. The hero, Monsieur Dusoleil, is established from the start as an ordinary civil servant very committed to his humdrum job, but whose unexciting life is irradiated by his beautiful but sad neighbor, Isabelle—my part. It then turns out that he has a magic gift: he can walk through walls.

Michel didn’t demand, in the American theatrical manner, that every character have a clear motivation and narrative. Even when working within fantasy, American directors want there to be a motive behind every actors’ action; James had worked for years with Sondheim, a different type of collaborator: detailed, painstaking and exacting. Michel wanted an accordion-filled lift-off to another dimension of beauty and tenderness. When my character, Isabelle, would enter the stage and start singing about going shopping, James felt it necessary to give me a shopping basket and other shoppers to walk amongst. Michel just wanted me to sing. James was all American logic and Michel, all French magic. Still, they worked without argument of any kind, perhaps because the Amour writer, translator and lyricist, Jeremy Sams, who was bubbly, erudite, scholarly, festive-natured—and an Englishman, possessed ample amounts of both their qualities and was the perfect go-between.

Michel didn’t demand, in the American theatrical manner, that every character have a clear motivation and narrative. Even when working within fantasy, American directors want there to be a motive behind every actors’ action; James had worked for years with Sondheim, a different type of collaborator: detailed, painstaking and exacting. Michel wanted an accordion-filled lift-off to another dimension of beauty and tenderness. When my character, Isabelle, would enter the stage and start singing about going shopping, James felt it necessary to give me a shopping basket and other shoppers to walk amongst. Michel just wanted me to sing. James was all American logic and Michel, all French magic. Still, they worked without argument of any kind, perhaps because the Amour writer, translator and lyricist, Jeremy Sams, who was bubbly, erudite, scholarly, festive-natured—and an Englishman, possessed ample amounts of both their qualities and was the perfect go-between.

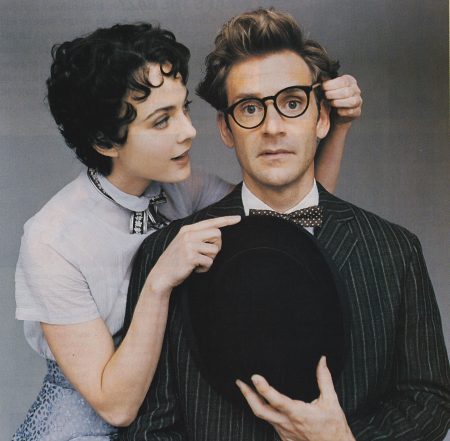

Michel met his first Broadway experience with his trademark ebullience and giddiness and wanted his long-awaited debut to be a wonderful success. The cast was a happy one, and my leading man Malcolm Gets, the same who would later tell me of Michel’s death was always deeply dedicated and relished every day, charmed by Michel’s warm nature. We prepared what we Americans thought a New York audience would want from a French musical, giving the painter a smock and a turned mustache so he resembled Gauguin, and knowing that there would need to be an Eiffel Tower somewhere in the advertising package. We prepared our music by singing in the chanson tradition, not using our voices harshly and loudly. Michel often said he did not like to be “wounded” by singers belting and yelling.

Those eleven weeks of rehearsal and performance (there were thirty-one previews and seventeen performances) were among the most extraordinary of my life. The producers had decided on a spectacular approach to the fantasy elements in the show, elements that might perhaps have been better dramatized by more indirect and stylized means. A musical about a man walking through walls doesn’t necessarily need walls to walk through—tell the audience that he is walking through walls, and, though the walls are merely lines on stage, they may be in a better mood to believe it.

But we were given elaborate stage machinery. I distinctly remember the evening that the “Boulangerie” set fell straight forward into and onto the audience. The walking through walls “concept” consisted of asking Malcolm to walk through a series of fat, vertical rubber bands, painted to match the doorframe, which he was to deftly separate with his hands in a swimmer’s motion, and pass through them, but instead they wiggled after he was through, or worse, frequently caught his ankles. One night, I was supposed to be singing on my second-story balcony, simply holding the laundry basket as it rested peacefully on the balustrade. I had an aria of longing and loneliness complete with some very soft but high vocal notes. Somehow, the set’s machinery must have experienced some tangled metal wires behind the walls: my balcony suddenly lurched sideways. I clutched the basket so it wouldn’t slide to the ground, and heard the creaking sounds of metal growing tense, as if I were on a ship that was about to give way. At an almost impossible diagonal, the set stopped its efforts and I was suspended twenty feet above the stage trying not to slide to the ground, hearing the distant moan of many unhappy metal wires. I tried to sing as delicately as possible, without looking down, hoping not to further upset the machinery. As I finished the high note ending, the curtain tenderly and gracefully descended and, once out of sight of the audience, the crew raced to my aid. After a brief intermission, we resumed the play. The producer called me that evening to thank me for my composure.

Amour got mixed, but many wonderful reviews, and was certainly what I think in France is called a suces d’estime. Michel was nominated for two Tonys, the American theatrical equivalent of Oscars, and so was I. But, as I had secretly feared, a New York audience wasn’t accustomed to this kind of music. Just down the street, the rock and roll musical Hairspray became the hit of the season. If we were working in watercolors as if by Thierry Duval, that fast and loud show was saturated, fun and self-evident like Andy Warhol’s pop art. Commercially, it was no contest.

Yet I remained proud of both my composure and the production and one night, a year after the show closed, I proudly walked my own copy of the opening night poster into the Joe Allen restaurant in the theater district—a place where, by a mordant tradition, all the famous Broadway “flops,” such as Mary Tyler Moore’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s as well as Dance of Vampires and Moose Murders, are immortalized on the walls. The criteria to make the wall is that the show has to run two weeks or less, and we just qualified.

I think the maître d’ was surprised by my chipper and proud appearance at the doorstep with the poster—but I wanted Amour to always be remembered, on any terms that anyone wanted to remember it. The poster, a secret signal for me that commercial failure has little to do with artistic pride, or values, is still there on a wall that no one can walk through.

After Amour closed, Michel and I appeared soon after in a series of jazz concerts together at Dizzy’s Jazz Club at Lincoln Center for the Mabel Mercer Foundation, and again at Catalina’s Nightclub in Los Angeles where I experienced the way that Michel performed his trademark jazz shows. All was spontaneous, unrehearsed and utterly relaxed. Michel invited me onstage to sing, from his musical and from his hits, and we had a wonderful time.

Then, two years after Amour, Michel said that perhaps we should conceive an album together. Michel came to Manhattan and we planned to spend a few days exploring his songs.

It was Valentine’s Day when Michel knocked on the door of our Soho loft. I had boundless free time to welcome him and share a few days together. At the door, my husband, Patrick McEnroe, greeted Michel in perfect French—Patrick won the French Open Men’s Doubles title in 1989 and has always had a strong attachment to France, in part, I have to say, because he had met a French model during his tennis travels and dated her for many years. (In the early months of dating Patrick, a French woman occasionally called his apartment; I would pick up the phone and say fluently, in French, the sentence: “I’m sorry, he is not home. No, I don’t think he’ll ever be home.” It was my first perfect French sentence. “Monsieur, n’est pas ici. Non,je ne pense pas qu’il sera jamais a la maison.” (Michel’s influence, I suppose.)

I had spent two weeks collecting every song Legrand had ever written into a massive binder. And I mean every. In anticipation of his arrival, I discovered that a New York musician had a comprehensive collection in his apartment. There were hundreds of songs, on faded pieces of paper which he had somehow been able to collect—songs that were discarded from Legrand films, versions of songs that only an insider would possibly have had. The musician wouldn’t let me take the whole collection at once, and so I found a copy-shop down the street. I would take one huge pile to the shop, do the Xeroxing and come right back to his apartment.

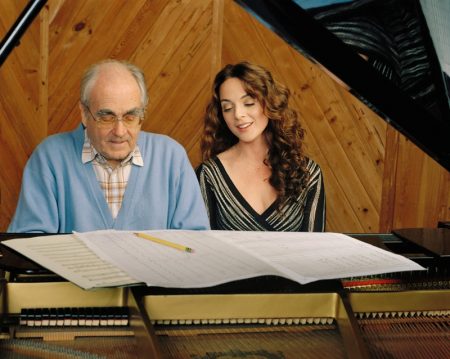

It took about six hours a day, but when Michel arrived at our Soho loft, I had all his music alphabetized and hole-punched in the largest binder I have ever owned. Once we finished our muffins and coffee and settled at the piano on that first rehearsal day, Michel recognized the preparation I had undertaken. He started to turn the pages, noticing songs he had completely forgotten that he had written. We went song by song. He would say “Oh, this is a good one for you,” or he would briskly move on. He gravitated to songs that were tender, caressing and had a certain refinement of language, with difficult melodies I could make sound conversational. He would ruminate on how a certain song belonged only to, say, Sarah Vaughn, or Blossom Dearie, or Barbra.

It took about six hours a day, but when Michel arrived at our Soho loft, I had all his music alphabetized and hole-punched in the largest binder I have ever owned. Once we finished our muffins and coffee and settled at the piano on that first rehearsal day, Michel recognized the preparation I had undertaken. He started to turn the pages, noticing songs he had completely forgotten that he had written. We went song by song. He would say “Oh, this is a good one for you,” or he would briskly move on. He gravitated to songs that were tender, caressing and had a certain refinement of language, with difficult melodies I could make sound conversational. He would ruminate on how a certain song belonged only to, say, Sarah Vaughn, or Blossom Dearie, or Barbra.

Those songs that Michel was sure “belonged” to me had a sort of purity to them, with both a fine-schooled quality and an unguarded almost hippie sensuality. I kept lists and he taught me melodies and we sat there day after day for a week. Occasionally, he wanted me to watch a movie that included his music and if I didn’t have a videotape of it, he called his manager and asked him to deliver it. We watched Cleo from 5 to 7 as well as his only directorial effort Five Days in June. (I must say my husband was a very dedicated assistant, running back and forth getting us baguettes and soda water as we tirelessly worked those days, neither me or Michel even slightly stopping in our energy to research and imagine a recording project. Patrick just kept running out to get us food to keep us alive.)

Those days in New York, we created a list of fifteen songs, and discussed how each song would feel—sometimes imagining a musical arrangement that would be spare and haunted, such as the lonely song “Martina” (about a child who was never loved), sometimes otherworldly and terrifying for a song like “I Was Born in Love with You”—meant “to sound like love that reaches beyond time,” across lifetimes, inspired as it is by the story of the great Emily Bronte novel Wuthering Heights. On the last day in my apartment, Michel even called the lyricists Alan and Marilyn Bergman on the telephone: “I need a new verse for Melissa! For ‘You Must Believe in Spring!’ Now, now! It’s too short! Too short!” Mere hours later, a fax came through from the Bergmans, with a new verse, adapted to that post 9/11 moment. That was what Michel’s energy could produce in others.

I will never forget the moment when he stood up, pacing around my hardwood floors, and said: “Melissa, it will be oceanic… and intime.” Oceanic and intime: I couldn’t have said it better. I, too, wanted to create the gentlest music imaginable, but with a vastness too, an embracing quality. It was that idea of music both orchestral and intimate that eventually became the ambitious symphonic recording called Legrand Affair produced by the legendary Phil Ramone.

He decided to record the album with a hundred-piece Belgian symphony. When in the summer of 2005, I ultimately walked into the concert hall in Leuven—a concert hall because there were no studios large enough for the symphony Michel had assembled—I was moved to tears. I had just arrived by train from London and was fifteen minutes late, and the symphony had already started playing. My hand went straight to my mouth. I had never heard the sound of 100 musicians playing before, but Michel had known just what he wanted.

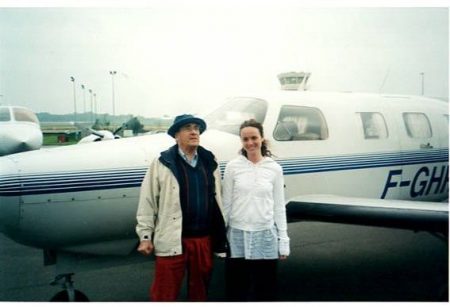

It’s almost impossible to believe what an ordinary day with Michel could be like. Once, just as we were completing recording in Belgium, Michel suddenly asked if Patrick and I would like to fly with him to Spain for a quick vacation. We shrugged and agreed. Only after we got to the airport did we realize that he really meant “fly with him”—he was the pilot of his own tiny plane, and flew us out through a rainstorm over the Pyrenees. At that point, I had a CD that Phil Ramone had handed me of the sessions—a rough mix of the symphony tracks. As I sat in that tiny airplane, piloted by Michel, I put my headphones on and listened to the oceanic symphony we had just finished recording the day before. There I was literally in mid-air, literally in the clouds! Patrick took a photo of me with the headphones on, in the plane, laughing at the incredible whirlwind of this blessed moment in life.

It’s almost impossible to believe what an ordinary day with Michel could be like. Once, just as we were completing recording in Belgium, Michel suddenly asked if Patrick and I would like to fly with him to Spain for a quick vacation. We shrugged and agreed. Only after we got to the airport did we realize that he really meant “fly with him”—he was the pilot of his own tiny plane, and flew us out through a rainstorm over the Pyrenees. At that point, I had a CD that Phil Ramone had handed me of the sessions—a rough mix of the symphony tracks. As I sat in that tiny airplane, piloted by Michel, I put my headphones on and listened to the oceanic symphony we had just finished recording the day before. There I was literally in mid-air, literally in the clouds! Patrick took a photo of me with the headphones on, in the plane, laughing at the incredible whirlwind of this blessed moment in life.

Landing for a picnic lunch, we had hardly caught our breath when Michel happily explained that he was due that night in Andorra for a concert with Chucho Valdes, and we had been drafted as his drivers. There we were in the front seat of a small French car, navigating our way across the terrifying corkscrew mountain roads, while Michel practiced piano in the back seat on a specially constructed wooden keyboard. (“Can you please go straighter!” he demanded of my poor husband.) The concert, when it happened, was a hurricane force of free music, with dueling pianists scatting on his classic “Watch What Happens,” stretching it to fifteen ecstatic minutes.

Michel could listen, too, as well as perform. He loved that I saw “The Windmills of Your Mind” as a poem about insomnia, which I have struggled with one and off all my life and concentrated on orchestrating my interpretation. He accomplished this by a swirling, arching and revolving orchestration that was both dizzying and achromatic at times. As I listened to our symphony tracks on that flight over the Pyrenees, and even now years later, I recognize how deeply Michel had understood my emotions and how precisely he wove my own feelings into his arrangements.

I was fascinated by Michel as a man. He was magnetic, with that kind of self-enclosure particular to men of genius. I remember him telling me his opinion of love and women. He said “the music comes first. If a woman interferes with my music, if they want to stop me…no.” But his life was filled with positive and empowering relationships with women, from Agnès Varda to Barbra Streisand to me, and, most obviously, with Marilyn Bergman. Those relationships were never like that of an artist feeding a mannequin or “muse.” They were equal.

There was nothing remotely erotic going on between Michel Legrand and me. Sometimes, yes, we were flirtatious. But almost always serious, platonic and focused. Sometimes we were on the edge.

Nothing erotic between us, but something erotic around us: my husband and I were trying all that year, as we worked on the album, to get pregnant. My OB/GYN had told me that it was time to become a mother if we wanted to do it. I can remember being in Manhattan—before we went away to Brussels—walking along the streets of Soho and listening to a recording on my headphones. I was listening to Michel’s song “Something New in My Life”, sung by Johnny Mathis. Michel’s music seemed to be saying to me, you should try to have a child.

Later that summer, returning to America after our recording and travels to Spain, Patrick and I conceived a child on our first evening back in our home in Manhattan. The miracle of a first child, fertility and possibility, the excitement of all of this is forever entangled in my memories of Legrand and a hundred musicians creating the stuff of dreams.

Looking over the narrative of my life from my father’s interior life, to my parent’s erotic life, to my own life with Michel in the mentor/muse balance, making professional life more magical than professional…and ending with me pregnant with my first of three mythic daughters, seems the stuff of dreams. Singing new vocal tracks, in New York City alone with Phil Ramone months later, with my belly full and round, my soon-to-be-born daughter, Victoria, kicking and moving inside me, I thought how moving it was that a baby was with me, in me, surrounded, too, by all that music. “Music is feeling, then, not sound,” wrote Wallace Stevens. And Michel was a uniquely feeling musician. The most exquisitely emotional days of my life—as a person, a child, an actress, a new mother- were set to his soundtrack, ignited by his mind.

Will I sing his music again, on the theater stage? There are scripts I want to study, his versions, unproduced in America, of Marguerite or Madwoman of Chaillot. Perhaps his dramatic work, as with Amour, never fully succeeded for a reason. His is not character driven music, about people weighing actions. His songs don’t sort through a problem. His songs are the emotions beneath the problem. A Legrand song is often an unending spool of emotion, action as a dream, an enchantment, and so beautiful that you feel lost in it.

I have spent many of my recent years singing the theater music of perhaps the other “God” of this generation, and a very American one, Stephen Sondheim. Utterly unlike as men—Sondheim is as much an icon of the gay-Jewish New York sensibility as Legrand was of the romantic-lyric French kind—Sondheim’s music and lyrics are nearly painful in their examination of the intricacies of the human mind and his lyrics attack the ambivalences of very specific characters making very specific decisions. Sondheim has his own kind of romanticism, singed by his ruthlessly intelligent lyrics, always asking the singer to welcome the conflicting and contrary emotion to the one we are feeling. Singing Legrand can be like swimming in a crystal clear blue sea that supports your limbs and makes you marvel at the wonder of being alive; Sondheim can be that same sea, but after your parents have warned you about the sharks you’ll meet if you go too far; you swim, enjoying the coolness on your skin, the glorious depths and mystery of your environment, but always on the lookout for shadows. As a singer, I run to Paris and Michel Legrand’s music for its unique ability to intoxicate me with a sense of the delight, delicate melancholy and unashamed sensuality of life. I believe his music belongs in the theater and I am determined to try it again.

Not long after Michel’s death, I saw James Lapine at a small intimate memorial for Legrand, and at the moment the Music Box Theatre dimmed the lights of its marquee in his honor, James turned to me with a bittersweet smile and said, “We had fun, didn’t we?” He was appreciating Michel’s infuriating sweetness now that we stood, arm in arm, without him. Sometimes we realize how delicious someone was once they are gone. We realize how they never seemed willing to stop sparkling, and one day they aren’t there. Like our parents. Like our children.

I will always hear Michel’s voice on that morning he said “Melissa! Hurry! Come!” He was inviting me to more than a writing session. His voice remains an invitation to live.