A Noir Nightgown: A Novella

by Adam Gopnik

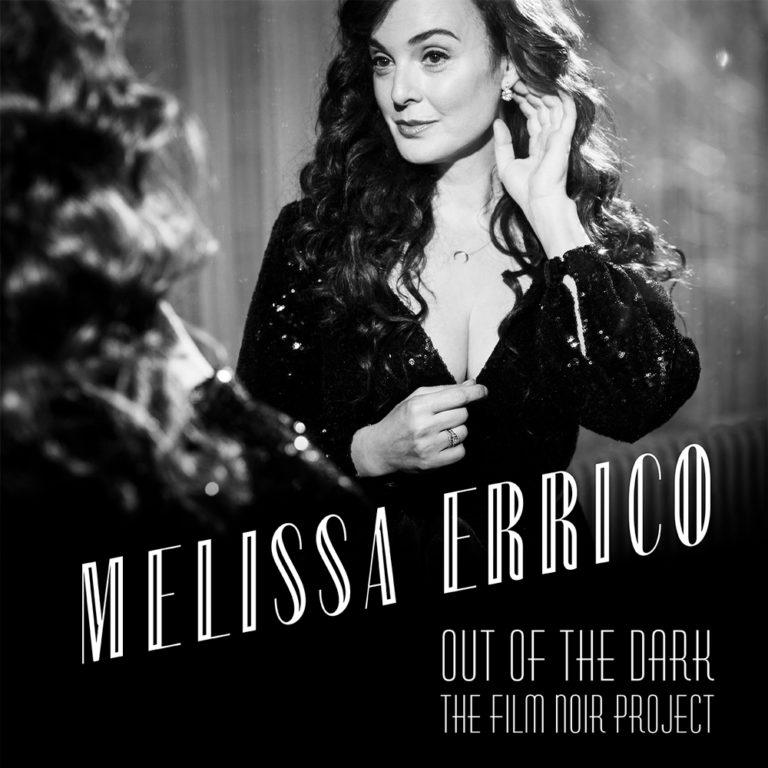

The following tongue-in cheek, yet heart-on-its-sleeve novella is meant to locate us, playfully, in the world of this recording, and, more soberly and precisely, in the inner life of its heroine, the imaginary woman on the cover:

This novella-movie of the mind is set in the 1940’s, of course; when else for Noir? But it’s a spiritual, psychic 1940’s, a dreamtime 1940’s of the mind, not fixed in space and time. It is an era of feeling that stretches out into the 1950’s for some cooler sounds, edging into technicolor movies and West Coast jazz, and seeps back into the 30’s for a kind of brittle humor.

Our heroine, the Far-From-Fatal Femme Fatale—call her the 5-F, in honor of the draft designation—lives by night and sleeps, mostly, by day. It is an occupational necessity. She is a singer—in her time, as the war began, quite a famous one, a girl singer with a big band, like Helen Forrest or June Christy. But then came the legendary musician’s strike—in our tale, the musicians’ strike lasts for years and hangs over the head of New York for a decade, like a dust storm.

She has a slightly unusual background for a singer on 52nd Street. She comes from a modestly fancy family in Bronxville, New York; Father a commuting stockbroker of the restless, unhappy Cheever kind; Mother a frustrated artist. She went to the local liberal arts college, Sarah Lawrence, and studied fine arts and classical singing, but then ran off on a dare, with a crazy wealthy girlfriend, in her junior year, to Paris, where she learned French and discovered jazz singing in a basement boite. She had a quick affair with Picasso on the Quai des Augustins—in those years, all American liberal arts majors were sleeping with Picasso, however briefly, collecting artists as their fathers collected art (though one Matisse was said to be worth two Picassos). Amour, amour, everywhere you looked for it. And now she—perhaps kids only others, perhaps kids herself—that she was the original of the curvaceous, mysterious girl before a mirror in his painting of the late thirties. She learned French and loved singing. Too many men in a Paris studio and the one right one not loved enough? Well, okay. Blame it on her youth.

When she came back to America, The Lure of The Life was too much for her; her world became 52nd Street and the city, and its music, and life. It was an audacious thing to do, but, given her gifts and appearance, not too audacious. Now, she sings at The Embers, a saloon on West 52nd Street in New York, right next door to the Onyx. Through the walls, she can hear the sounds of Art Tatum intricacies next door and, if the door is left open on a hot summer night, you can hear the thrum thrum left hand rhythm guitar beating of Errol Garner, working out the chord changes of “Misty.”

The Far-From-Fatal Femme Fatale wears a black sequin dress to perform her nightly three sets—seven, nine, and midnight. She thinks of it as her Noir nightgown. (At Sarah Lawrence, in a seminar on Joyce, she had misheard the phrase “Noir nighttown,” referencing Joyce’s Ulysses, as “Noir nightgown,” and the idea stuck deliciously in the taste buds of her sensual mind.) Her outer emotional gamut is brittle, wisecracking, sexy, self-confident—if there’s a man who can resist her, she hasn’t met him yet—rising at midnight to a desperate search for the oblivion of sex and sleep, and then subsiding at noon into making her bookings and picking her set list. Her gaiety and appetite are real; she will go her own way, checking her heart. Her solitude is all inside her.

Hers is a street of limitless art and extravagant talent—but of mundane saloon manners and expectations. Sublime music rises, but the guys and girls at the bar only occasionally hush to hear it. (Our 5-F is born a little out of time: ten years later, she might be Peggy Lee singing with George Shearing—though twenty years more on, she might be Beverly Kenny or Susannah McCorkle, dying for the love of great songs and the absence of an audience.) But for now, she is at best a cult figure, attracting a small but avid following—though, as she knows ruefully, for the majority of people who come into the bar, it is just a bar, where they seek their own oblivion, and the girl singer is just a girl singer with a piano player. They look up when she sings a hit, like “Written in The Stars,” and smile appreciatively, but then they turn back to the highball in front of them. She doesn’t mind this, entirely; she accepts and even relishes the poetry of saloon indifference. (She does not drink. It is bad for her voice, and she lives in terror of sloppy women drunks. She does smoke, Pall-Malls, because, though bad for her voice as well, the little ritual of case and match and wreathing smoke rings she finds sexy and irresistible.)

There are many men in her life—she is, or can be, fatal when she chooses—but two above all: her true love, a French writer, a sort of cross between St. Exupery and Albert Camus, though with a Danny Kaye accent—played for our purposes in alternate scenes by John Garfield and Jean Gabin. (Recall: this is a changeable collage of kinds, a dream of a period.) Half-French, half-American, he is a dark philosopher and mordant fabulist of modern passions. They had met in Paris, where he was attached to the caf philosophy life. He amused her with his Gallic shrug and suspiciously smooth and cynical-seeming aphorisms: “Quand on a pas ce que l’on aime, il faut aimer ce que l’on a,” he had said, a phrase later to inspire a Broadway lyric, and “Life is simple: On vit, on aime, on ment, on meurt.” Like all French cynics, he is a disappointed romantic, and after an extravagant flirtation, they had settled on an epistolary love affair, all text, in both their languages. Then, after he escaped the fall of France, they had shared wild love, a champagne cocktail of sex and lore, a lure of oblivion, in his tiny New York apartment, where he spent mute months plotting with the other French exiles in New York. But then, he had parachuted into France a year and a half ago for the OSS. No one has heard of him, or from him, since, and much of the day she spends thinking helplessly of him. She imagines him, hopefully, still undercover in Paris boites or in the South of France, helping allied airmen escape or making sketches of the train travels of German trains.

She knows that such flyers disappear and then reappear—St. Exupery himself was lost for months in the desert, but came back, and with the legend of the Little Prince under his arm. But when she despairs, she believes that he is lost already, gone for good. Not a word in two years. She keeps around her throat a half moon he gave her on the night of his departure. He haunts her heart and is the one love that vanished, the only man who got away. Not a morning when she opens up her eyes and doesn’t think of him.

But she is far from a defeated woman. Her diamond earrings, which she adjusts tonight complacently in the tiny dressing room mirror as she gets ready to sing, with a cat-that-swallowed-the-canary-complacency crossing her features, are a gift from the owner of the club, her sporadic and intense lover, and fellow oblivion seeker. He is the Kirk Douglas character in the story, a gangster, yes, certainly, but smart and sophisticated in his way, and with a brutal charisma that she respects and finds magnetic. Like St. Exupery’s wife, when that French philosopher was lost for the first time over the desert, she refuses sadness as a matter of passionate principle. So, she meets him for semi-regular assignations in his penthouse room in the St. Regis, three blocks away—all girl singers need a protector, her worldly side tells her. She likes his smell, and size, and shamelessness. She swears him off, regularly, then succumbs again. She can check her heart in his presence as easily as men check their hats in the club cloakroom. But he somehow has a knack for reclaiming it again.

On the imaginary night in which these songs are set, she enters into a kind of dark night-town journey into the soul, with the seven-o’clock early set, thinking of the mysteries of fate. Her friend, the singer Matt Dennis, has written a new song, “Angel Eyes,” for her, rueful and sad, and she starts her set there, biting out the soon-to-be-famous words of the release with appropriate irony. “Drink up, all you happy people”… She and her pianist have a slightly psychic connection—he is not, like Shearing and Tatum, those other geniuses of the street, actually blind—but he is often silent, occasionally offering a wise word or two in an argot of his own, like Lester Young, only even more gnomic. They luxuriate in their psychic understanding. She loves the club for representing so perfectly the fallen world she’s in, thinking of how closely allied the damned and the beautiful always are, and how that alliance haunts her.

Haunts her! Now, thinking of her lost love, she feels again how haunted her heart is by him still. He is always here, and never here. At times, she becomes enraged with him—for leaving her, for putting his “work” first, work which other men could have done. But his ghost is with her always… not a word in so long? An old French girlfriend wanders into the club, which reactivates her mind to things French. She recalls together how they had conspired in Paris.

The gangster who owns the club comes in, looking cool, hair swept back, bad and, in his way, beautiful. She notices that one of his yeggs passes him, under the table, a bag of… something? What is it? What contraband? Drugs or jewels? Her gangster places it in a lock box she has seen him hold before, as though it contains his most precious possession. She looks him directly in the eyes, searchingly, trying to remind him that he has her, not her heart. He orders her to play “something lively, something loud,” and, with her French friend in the club, and her half-French lover on her mind, she launches into a strange surrealist screech; “Amour, Amour” she sings out loudly. While she does, and her pianist percusses on the piano, there is a commotion in the club…

Later she keeps an assignation, with the gangster, in the hotel room from which he surveys his night-empire… they make love desperate, in the dark, seeking oblivion. They are silent partners once again: hotel room, cigarette smoke, neon light through the venetian blinds.

After sex, he is laughing, and can’t resist telling her that he had had her sing the “fast, loud one” so that his yeggs could jump a competitor gangster who had wandered into the bar, stabbing him to death right in the club, with her music there to cover the commotion. Her blood grows chill at his boastfulness—she sees the depths of his cruelty and shallowness. She waits for him to fall asleep, and walks out into the gray dawn, vowing never to return. Farewell, you lovely bastard. She looks back up at the hotel room, where she now senses nothing but grief and recognizes the spell it cast on her. A constellation forms wherever sex was seized on. She takes the jewel box with her, conscious that it must hold some secret of his that she can use to protect herself against his vengeance. On her long five a.m. walk through the dark, still sunless skies, she speaks to herself, in French, for his absent benefit, of the almost suicidal solitude she finds herself in now.

Her steps take her back to The Embers, where her patient pianist uses his matchless fingers to unlock the box. The lock box contains… that last two years of letters from her philosophical Parisian lover! Patiently posted obliquely from his hideaways in France, by way of the Resistance HQ in London, sent to the club—and cruelly intercepted by her gangster. She sees at a glance… that he is safe, though lost for a long time, still safe! Safe! And yet, it seems that he has despaired of her—her indifference to his letters, her casualness about his fate, has left him hopeless—and who is this “Laure” he mentions? Merely a comic misunderstanding, but so cruelly enforced, and, now, he is coming back on a liner… she imagines the two of them driving away, from war and pain, out onto a highway in post-war America, past all detours and distractions, driving towards love.

This may happen, yet. Could it happen, again? Easy openness, nothing clandestine, just a man and a woman driving through the night? Much repair to be made, many detours ahead. But it could happen. The man that got away, home again.

It is noon, and she hasn’t slept, but there is hope and, in any case, the darkness that surrounds us is essential if we are to see the light, she now believes. All alone in her tiny dressing room- where else can a showgirl go?—she curls up and sleeps. Ah, sleeps! Still in her dress, her heart marginally lighter. She is, for a moment, out of the dark.