Legrand Affair

“Sensuously alluring” “with luscious and emotive strings produced by Phil Ramone.”

Track List

Disc One: Legrand Affair

- I Was Born In Love With You

- The Summer Knows

- His Eyes, Her Eyes

- The Windmills Of Your Mind

- I Will Wait For You

- In Another Life

- Martina

- Dis Moi

- You Must Believe In Spring

- What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life

- How Do You Keep The Music Playing

- Something New In My Life

- Maybe Someone Dreamed Us

- Once Upon A Summertime

- Celui-La

Disc Two: Bonus Material

- I Haven’t Thought Of This In Quite A While

- Little Boy Lost

- What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life?

(Feat. Russell Malone) - The Way He Makes Me Feel

- Hurry Home

- Something New In My Life (Studio Demo)

- Maybe Someone Dreamed Us (Studio Demo)

- The Summer Knows (Studio Demo)

- Once Upon A Summertime (Studio Demo)

- The Windmills Of Your Mind (Studio Demo)

- Dis Moi (Studio Demo)

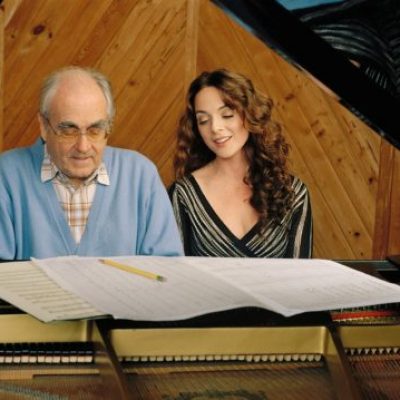

- Michel & Melissa At Work

Legrand Affair

Liner Notes

I can still hear Michel Legrand’s voice in my head: “Melissa! Hurry! Come!” This was morning at the Music Box Theatre, an early rehearsal during the first previews of the Broadway musical Amour which Legrand wrote and I starred in 2004.

It was 10:01 am and we were all moving slowly, nursing coffee cups in the palms of our hands. We had performed the show the night before and were still easing into the day. Michel never wanted to waste a minute. He pulled on my arm, speaking fast in heavily-accented English, insisting that we must find a piano. As we scurried to the downstairs theater lobby, he told me he had completed a new song for my character, Isabelle, and it would go into the show that evening. We flew down the gilded stairs of the theater, and I tucked beside him on the piano bench. What I remember most was the change in Michel’s body language as he shared his new music. Once at the piano, he slowed down and became absorbed. He would rush you as if to an American ice cream parlor on a crowded summer afternoon—and then offer you a slowly simmered French meal. I sat as he played, and marveled quietly when his hands turned the melody unexpectedly, a new minor key, a delicious twist that only he could have invented. Of course, the song “Other People’s Stories” was beautiful, perhaps the best remembered in the show. And it was in Amour by 7:00 pm that night, typed hurriedly by a stage manager and taped into a magazine prop so I could literally read it as I sang it in front of a thousand people.

This mix of wild energy and plaintive emotion, I would learn in our weeks of rehearsal, governed Michel’s extravagantly well-lived life. Music was urgent to him. Well, almost everything was urgent to him—try hailing a New York taxi with him, oh! the impatience—and then at the piano, he was transformed and calm. Stilled by the beauty of his own sublime music.

I heard his voice again in my head on a cold Saturday morning earlier this year when I got a text from the actor Malcolm Gets. “Michel!” is all the text said. It was 8:08 am. Directly below was a link to The New York Times announcement: Michel Legrand had died the night before. I was stricken. Though I hadn’t seen him for some time, he was always in my mind. We have so few mentors and muses in a lifetime, and Michel was one of mine—as, I realize now, I was one of his. That an Italian-American girl from Manhasset (sort of the Neuilly of Manhattan) should have become so intimately involved with one of the greatest of French popular composers—perhaps the greatest French popular composer since Offenbach—now seems to me one of the great strokes of improbable good fortune of a lifetime.

I was born in the early 70s and I cannot recall a day of my life where Michel Legrand wasn’t a part of the fabric of our family. My father is a doctor, a prominent Manhattan orthopedic surgeon, who grew up in a first-generation Italian family in a modest small house in New Jersey with two working parents. My father’s sister was eight years old when she began playing the piano and my father, only four-years-old, grew transfixed by the instrument. He even slept under the piano, just to be near it. By the time he was a teenager, he was an accomplished classical pianist and was accepted at Yale University in 1957 as a scholarship student in music. My father paid for his college expenses by playing the piano at “socials” and university dances, leading bands and mastering the American Songbook from Gershwin to Cole Porter, becoming expert at jazz-based “popular” songs—and impressed by the exciting new sounds of a 22-year old Michel Legrand whose Dionysian album “I Love Paris” was instantly popular with American music lovers who marveled at his treatment of such songs as “Autumn Leaves” and “La Seine.”

I was born in the early 70s and I cannot recall a day of my life where Michel Legrand wasn’t a part of the fabric of our family. My father is a doctor, a prominent Manhattan orthopedic surgeon, who grew up in a first-generation Italian family in a modest small house in New Jersey with two working parents. My father’s sister was eight years old when she began playing the piano and my father, only four-years-old, grew transfixed by the instrument. He even slept under the piano, just to be near it. By the time he was a teenager, he was an accomplished classical pianist and was accepted at Yale University in 1957 as a scholarship student in music. My father paid for his college expenses by playing the piano at “socials” and university dances, leading bands and mastering the American Songbook from Gershwin to Cole Porter, becoming expert at jazz-based “popular” songs—and impressed by the exciting new sounds of a 22-year old Michel Legrand whose Dionysian album “I Love Paris” was instantly popular with American music lovers who marveled at his treatment of such songs as “Autumn Leaves” and “La Seine.”

At Yale, my father met my mother at a party—she approached his piano just as he was playing the Gershwin brothers classic “The Man I Love”—and they have been together ever since. Yet my father, for all his passion for music, became a medical student, and soon after graduation from medical school was drafted for the Vietnam War, where he was a medic in Saigon. My parents were separated and had a newborn son, my brother, Michael. One of the songs of their emotional life at that time was the 1964 Legrand classic “I Will Wait for You”—originally “Je ne Pourrais Jamais Vivre Sans Toi” from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. I realize now that it was written about an imaginary couple separated by the Algerian War. It became real for my parents as a song about the Vietnam one, ironically a war inherited by America from France.

For me, from the first, Michel Legrand’s music was above all physical. Its presence literally transformed the room in which it lived. My father, back from Vietnam, would come home from the hospital and play Chopin for hours. But then he would meander over the keys for another half hour or more, playing Legrand. I thought Chopin wrote “Windmills of Your Mind” until I grew old enough to ask him what those beautiful sounds were. Michel Legrand’s name was mentioned to me with the same seriousness that my father would mention Debussy’s or Ravel’s or Rachmaninoff’s. He revered Legrand and meditated on the exotic chords, playing them as if they were sacred, letting the effect of their sheer beauty wash over our house and over his own spirit. My father was a reticent man, a surgeon ruled by his beeper (a pre-cellphone device attached to the waist of his pants) which would buzz when he was needed at the hospital.

For me, from the first, Michel Legrand’s music was above all physical. Its presence literally transformed the room in which it lived. My father, back from Vietnam, would come home from the hospital and play Chopin for hours. But then he would meander over the keys for another half hour or more, playing Legrand. I thought Chopin wrote “Windmills of Your Mind” until I grew old enough to ask him what those beautiful sounds were. Michel Legrand’s name was mentioned to me with the same seriousness that my father would mention Debussy’s or Ravel’s or Rachmaninoff’s. He revered Legrand and meditated on the exotic chords, playing them as if they were sacred, letting the effect of their sheer beauty wash over our house and over his own spirit. My father was a reticent man, a surgeon ruled by his beeper (a pre-cellphone device attached to the waist of his pants) which would buzz when he was needed at the hospital.

But there were afternoons when he knew he wasn’t on-call and had put aside a few hours for his music. I liked to come in, instead of doing my homework, and listen. I didn’t quite grasp that the composer Michel Legrand was alive, and, say, that Chopin was long gone. Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Legrand…they all seemed to exist in one historic time. My father told me how he loved the movies they were from, but said I couldn’t see them “yet”—never explained the plots, or even played the videos for me. I sensed there was something “grown-up” about The Summer of ’42 or The Thomas Crown Affair, and I wasn’t quite old enough to entirely be let in on all the secrets.

The father-daughter seduction in this coded dialogue was bonding and I loved those stolen hours where the doctor wasn’t running off, or exhausted asleep in his suit. My mother loved the songs too and I can remember countless times where he would play ”The Summer Knows,” and she would waft into the living room, perhaps from the kitchen around dinner time, and fall on the sofa in a swoon. She loved when he abandoned the intensity of his classical practice—which she also found ruthless and relentless—and played a Michel Legrand classic like “His Eyes, Her Eyes” or “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?” During my teenage years, I became aware of the erotic and mysterious communication in my home. I was always so happy to see my mom walk into the living room, her body language soft and supple, as she lay down on the sofa, letting her hair fall over its edge. She sometimes seemed aware I was delighting in her, and my father enjoyed his success in thrilling us both. I wanted them to kiss—and she occasionally did come over and give him a big long kiss, as he played somewhat slower but hardly missed a note on the piano.

The father-daughter seduction in this coded dialogue was bonding and I loved those stolen hours where the doctor wasn’t running off, or exhausted asleep in his suit. My mother loved the songs too and I can remember countless times where he would play ”The Summer Knows,” and she would waft into the living room, perhaps from the kitchen around dinner time, and fall on the sofa in a swoon. She loved when he abandoned the intensity of his classical practice—which she also found ruthless and relentless—and played a Michel Legrand classic like “His Eyes, Her Eyes” or “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?” During my teenage years, I became aware of the erotic and mysterious communication in my home. I was always so happy to see my mom walk into the living room, her body language soft and supple, as she lay down on the sofa, letting her hair fall over its edge. She sometimes seemed aware I was delighting in her, and my father enjoyed his success in thrilling us both. I wanted them to kiss—and she occasionally did come over and give him a big long kiss, as he played somewhat slower but hardly missed a note on the piano.

Michel Legrand was, in our home, a sort of portal to freedom and sensuality. Hiding the plot lines of the movies from me, my Dad winked and smiled, implying by his winking omissions that there was more out there than I knew now. Legrand was a keyhole, through which I saw a light, knowing there were other rooms in my own life to come.

Then, one day in 2002 when I was living in Hollywood, I was approached by my manager in a fancy Beverly Hills talent office. I had done seven failed television pilots, making it my goal to get the number up to eleven as George Clooney had before his first success—thinking that was a magic number where perhaps I could have a break-through. My manager handed me a fax that had just come to the office from New York City. It said that there was an audition in New York and the director James Lapine would like me to come in. Apparently, there was a musical in Paris called Le Passe Muraille and it was transferring to Broadway—with music by Michel Legrand.

The paper seemed to glow in my hand, as if it had a light shining from inside it into my soul. I turned to my Hollywood manager and cried out, “Michel Legrand…Michel Legrand!…wrote a musical!” She turned to me, matching my smile with her own, and said “I know, I know! I love her!”

So, I left that agency and that manager, permanently as it turned out, and flew to New York to follow the promise of that illuminated fax. I called my father at once and told him I had gotten the lead role in a Legrand musical, now re-titled, for American audiences: Amour. James Lapine explained that they had to title it Amour because Americans only know three French words, the other two being “café” and “croissant”. My father, now age 80, still recalls that phone call of mine and his eyes light up, incredulous, at how strange and lucky that life twist still seems: “I knew it meant you, we, might actually meet Michel Legrand.”

And so, we did. Michel and I had an immediate rapport. We merged. He often told me he loved the classical purity of my voice and the clarity of my diction. I had been trained to sing clearly, not ‘belt’ or yell, and found the sound of my voice honest and direct, and once he even told me “Yours is the voice I hear in my head when I write.”

Amour got mixed, but many wonderful reviews, and was certainly what I think in France is called a suces d’estime. Michel was nominated for two Tonys, the American theatrical equivalent of Oscars, and so was I. But, as I had secretly feared, a New York audience wasn’t accustomed to this kind of music.

Then, two years after Amour, Michel said that perhaps we should conceive an album together. Michel came to Manhattan and we planned to spend a few days exploring his songs. It was Valentine’s Day when Michel knocked on the door of our Soho loft. I had boundless free time to welcome him and share a few days together. At the door, my husband, Patrick McEnroe, greeted Michel in perfect French—Patrick won the French Open Men’s Doubles title in 1989 and has always had a strong attachment to France. I had spent two weeks collecting every song Legrand had ever written into a massive binder. When Michel arrived at our Soho loft, I had all his music alphabetized and hole-punched in the largest binder I have ever owned.

Once we finished our muffins and coffee and settled at the piano on that first rehearsal day, Michel started to turn the pages, noticing songs he had completely forgotten that he had written. We went song by song. He would say “Oh, this is a good one for you,” or he would briskly move on. He gravitated to songs that were tender, caressing and had a certain refinement of language. Those songs that Michel was sure “belonged” to me had a sort of purity to them, with both a fine-schooled quality and an unguarded almost hippie sensuality.

Once we finished our muffins and coffee and settled at the piano on that first rehearsal day, Michel started to turn the pages, noticing songs he had completely forgotten that he had written. We went song by song. He would say “Oh, this is a good one for you,” or he would briskly move on. He gravitated to songs that were tender, caressing and had a certain refinement of language. Those songs that Michel was sure “belonged” to me had a sort of purity to them, with both a fine-schooled quality and an unguarded almost hippie sensuality.

Those days in New York, we created a list of fifteen songs, and discussed how each song would feel—sometimes imagining a musical arrangement that would be spare and haunted, such as the lonely song “Martina” (about a child who was never loved), sometimes otherworldly and terrifying for a song like “I Was Born in Love with You”—meant “to sound like love that reaches beyond time,” across lifetimes, inspired as it is by the story of the great Emily Bronte novel Wuthering Heights. On the last day in my apartment, Michel even called the lyricists Alan and Marilyn Bergman on the telephone: “I need a new verse for Melissa! For ‘You Must Believe in Spring!’ Now, now! It’s too short! Too short!” Mere hours later, a fax came through from the Bergmans, with a new verse, adapted to that post 9/11 moment.

He decided to record the album with a hundred-piece Belgian symphony. When in the summer of 2005, I ultimately walked into the concert hall in Leuven—a concert hall because there were no studios large enough for the symphony Michel had assembled—I was moved to tears. I had just arrived by train from London and was fifteen minutes late, and the symphony had already started playing. My hand went straight to my mouth. I had never heard the sound of 100 musicians playing before, but Michel had known just what he wanted.

It’s almost impossible to believe what an ordinary day with Michel could be like. Once, just as we were completing recording in Belgium, Michel suddenly asked if Patrick and I would like to fly with him to Spain for a quick vacation. We shrugged and agreed. Only after we got to the airport did we realize that he really meant “fly with him”—he was the pilot of his own tiny plane, and flew us out through a rainstorm over the Pyrenees. At that point, I had a CD that Phil Ramone had handed me of the sessions—a rough mix of the symphony tracks.

It’s almost impossible to believe what an ordinary day with Michel could be like. Once, just as we were completing recording in Belgium, Michel suddenly asked if Patrick and I would like to fly with him to Spain for a quick vacation. We shrugged and agreed. Only after we got to the airport did we realize that he really meant “fly with him”—he was the pilot of his own tiny plane, and flew us out through a rainstorm over the Pyrenees. At that point, I had a CD that Phil Ramone had handed me of the sessions—a rough mix of the symphony tracks.

As I sat in that tiny airplane, piloted by Michel, I put my headphones on and listened to the oceanic symphony we had just finished recording the day before. There I was literally in mid-air, literally in the clouds! Patrick took a photo of me with the headphones on, in the plane, laughing at the incredible whirlwind of this blessed moment in life.

Landing for a picnic lunch, we had hardly caught our breath when Michel happily explained that he was due that night in Andorra for a concert with Chucho Valdes, and we had been drafted as his drivers. There we were in the front seat of a small French car, navigating our way across the terrifying corkscrew mountain roads, while Michel practiced piano in the back seat on a specially constructed wooden keyboard. (“Can you please go straighter!” he demanded of my poor husband.) The concert, when it happened, was a hurricane force of free music, with dueling pianists scatting on his classic “Watch What Happens,” stretching it to fifteen ecstatic minutes.

Michel could listen, too, as well as perform. He loved that I saw “The Windmills of Your Mind” as a poem about insomnia, which I have struggled with on and off all my life and concentrated on orchestrating my interpretation. He accomplished this by a swirling, arching and revolving orchestration that was both dizzying and achromatic at times. As I listened to our symphony tracks on that flight over the Pyrenees, and even now years later, I recognize how deeply Michel had understood my emotions and how precisely he wove my own feelings into his arrangements.

Looking over the narrative of my life from my father’s interior life, to my parent’s erotic life, to my own life with Michel in the mentor/muse balance; professional life became more magical than professional. That same European summer ended with me pregnant with my first of three mythic daughters. It seems the stuff of dreams. Singing new vocal tracks, in New York City alone with Phil Ramone months later, with my belly full and round, my soon-to-be-born daughter, Victoria, kicking and moving inside me, I thought how moving it was that a baby was with me, in me, surrounded, too, by all that music. “Music is feeling, then, not sound,” wrote Wallace Stevens. And Michel was a uniquely feeling musician. The most exquisitely emotional days of my life—as a person, a child, an actress, a new mother- were set to his soundtrack, ignited by his mind.

I will always hear Michel’s voice on that morning he said “Melissa! Hurry! Come!” He was inviting me to more than a writing session. His voice remains an invitation to live.

— Melissa Errico